Somaliland has a population of close to 5 million people, and nearly all girls (approximately 98%) undergo female genital cutting (FGC) in the self-declared state. Most Somali girls are cut between the ages of 4 and 14 and are typically subject to FGC Type III (Infibulation) cutting.

In February 2019, Orchid Project held a Knowledge Sharing Workshop in Hargeisa, the capital city of Somaliland. Participants joined from grassroots civil society and government ministries, coming together to learn and exchange information around how to support abandonment of FGC. The workshop used UNICEF’s 6 Elements of Abandonment as a framework for participants to adapt to their own context.

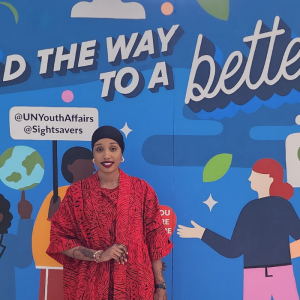

Muse at the KSW in Hargeisa, Somaliland.

Muse Jama was one of the participants at the workshop. Muse is the Programme Manager for Women Rehabilitation and Development Association (WORDA), an NGO based in Hargeisa that works to develop local communities in Somaliland and empower women through advocacy, enhancing education, skills training and provision of materials.

We spoke to Muse about the shifts in attitudes to FGC in Somaliland and how Orchid Project’s workshop can be useful in their work going forward.

“Female genital cutting is a social norm and social norms take a long time to change” said Muse when asked why FGC continues in Somaliland. “The process is seen as protection for the girl and for the family’s dignity. People think it is part of Somali culture and that they have to practice it.” In addition, Muse told us that FGC is viewed as a requirement for girls to be married, and has strong links to early marriage.

Muse’s work with WORDA aims to change perceived social norms such as FGC that have a consequence for the health of women and girls. They are reducing FGC in local communities by raising awareness about the healthcare risks. It is crucial, Muse says, that they don’t tell people to stop or show judgement; they must create a non-judgemental open dialogue with people to ensure that communities are heard and can discuss, and so they don’t feel that external concepts are being imposed. This approach can then lead to communities choosing to end cutting.

Female genital cutting is a social norm and social norms take a long time to change

Participants in discussions at the KSW in Somaliland.

Alongside their work to change social norms, Muse said they are starting to see some reduction in the prevalence of FGC in Somaliland, especially in urban areas. Awareness of the effects of FGC is, he says, lower in rural communities and as a result they are not seeing so much change. WORDA previously worked mainly in urban areas but will now shift its work to include rural areas to change harmful practices at a community level.

Somaliland is also, according to Muse, seeing a shift in the type of cut girls undergo from the pharaonic type (Type III Infibulation) to the sunna type, which can be Type I, II or IV depending on the context. In 2018, The Ministry of Religious Affairs in Somaliland issued a fatwa (Islamic law ruling) banning the pharaonic type of FGC, the most severe form of cutting. Muse believes there is confusion in the community about the fatwa, which adds to the challenge of ending FGC in Somaliland. A further challenge in local communities is the belief that the sunna cut is a religious obligation, despite FGC not being an obligation of any religion.

Despite these challenges, there is change happening. Muse and WORDA know that social norms are difficult to change but they are hopeful. By focussing on health complications and using ‘UNICEF’s 6 elements of FGC abandonment’, they know that they can support change around harmful practices at a community level.

Through attending the Orchid Project Knowledge Sharing Workshop, Muse says he “learnt how to conduct community dialogue and how to share experiences,” as well as the need for a safe space to share that experience in exchanges with the community. “Community Exchange” is one of ‘UNICEF’s 6 elements for FGC abandonment’ that form the framework for the workshop Muse attended, and he noted this will be essential to ending FGC within a generation in Somaliland. WORDA plan to review their strategy and think about how to use all of the elements to help accelerate an end to cutting.

To hear more from Muse, watch our video interview with him recorded at the knowledge sharing workshop in Somaliland this February.