On Saturday 15 June, Orchid Project’s partner Sahiyo launched ‘Faces for Change’, the first ever photo campaign to highlight that girls and women in India and across Asia are affected by female genital cutting (FGC). Faces for Change gives voice to the experiences of eight courageous women who have survived FGC, in a country where the government has not adequately acknowledged the scale and existence of the practice, and has denied there is enough evidence that FGC happens in India. The campaign launched in Mumbai on Saturday with an exhibition to showcase the photographs, and panel discussions with survivors, eminent doctors, religious leaders and child specialists.

We spoke to Sahiyo co-founder Insia Dariwala about the campaign and what she hopes it will achieve. Insia is an activist and an award-winning, international filmmaker currently based in Mumbai. She co-founded Sahiyo five years ago, coming together with four fellow FGC activists. Sahiyo is a transnational communications and advocacy collective, and works to raise awareness of FGC in South Asian contexts, with a focus on the Dawoodi Bohra community in India and globally.

Faces For Change Exhibition Launch, Mumbai, June 2019

In July 2018, Insia, through her organisation ‘The Hands of Hope Foundation’, launched ‘End The Isolation’, India’s first photo campaign to feature male survivors of child sexual abuse. The campaign became a movement and shone a light on abuse that was often swept under the carpet. Such was the effect of the campaign that the Government responded, leading to the Women and Child Development Ministry passing a resolution that provides equal protection to both boys and girls and views child sexual abuse in a genderless way. The Faces For Change campaign hopes to garner the same success that Insia saw through the End the Isolation project.

While research on FGC in India is scarce, Sahiyo’s initial studies estimate that at least 80% of women in the Bohra community have undergone the FGC, with girls typically cut at the age of seven. Girls are known to undergo Type I FGC (clitoridectomy, known as khatna amongst the Bohra community) or Type IV FGC, both of which are a violation of human, child and women’s rights.

FGC in India is believed to be most commonly practised within the Bohra community, however Insia told us that the practice “is no longer just a community issue, it is a country issue.” Sahiyo’s engagement with survivors on the ground has, Insia said, provided insights into the wider practice of FGC in India. Insia highlighted the Marakyaar community of Kerala, who also practice FGC and do so on baby girls who are a month old. The practice has also been reported to occur within other communities in India, including Suleimani Bohras, Alvi Bohras and other Sunni Muslim sub-sects of Kerala.

The Faces for Change campaign aims to be inclusive to the women and girls of every community that practices FGC in India, and has ambitions to grow to be a pan-Asian campaign. It will, says Insia, bring the focus onto FGC survivor voices and highlight their experiences in a country where the practice is not being acknowledged or addressed by government. Insia told us that by denying the experiences of women such as those featured in Sahiyo’s campaign, the government “negates their existence and trivialises the trauma that survivors have faced.”

Insia herself speaks from experience. Growing up her sister was cut but Insia was not. She wrote of her upbringing in a short story in 2016, “The Uncut” detailing how “when you’re not cut, you’re cut off” socially and that she grew up with a lot of low self-esteem as a result. Despite this experience and her work with Sahiyo and The Hands of Hope Foundation – Insia’s own organisation which actively works against sexual abuse and violence on children – she still had unexpected experiences documenting the survivors for Faces for Change.

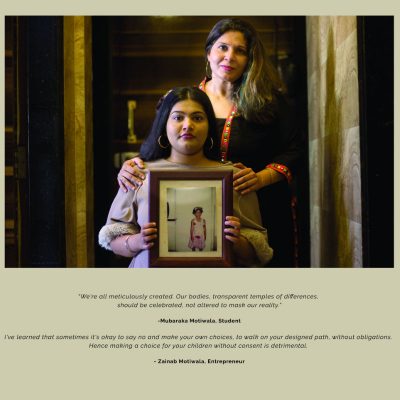

Image credit: Dipak Nayak

One such experience occurred when Insia went to take photos of a young woman who features in the campaign, and is a vocal member of the Indian survivor community. As they were preparing for the shoot, the woman’s mother walked in, and Insia approached her to join them. Insia said, “To my surprise, she said “yes”. By featuring two generations of women, the result is a really powerful image.” Insia recalls how “the mother did it (FGC) because she didn’t know it was harmful and she did what other people were doing. She was never happy with it.”

The power of the support lent by this survivor’s mother and the eight women of Faces for Change will, Insia hopes, ignite change. She said, “Faces for Change calls on the government to ban FGC. The scale of the challenge is daunting; not only have the government denied that there is evidence of FGC happening in India, they have also trivialised it and promoted medicalisation of the practice.”

Efforts to challenge the continuation of the practice and ensure the safety of future generations have even reached the Supreme Court, with an ongoing case being fought between pro-FGC campaigners and those who are against the practice. “Where you have 10 people saying it shouldn’t happen,” Insia says, “you have 10,000 saying it should. That’s very intimidating.” Despite the challenge they face, Insia and Sahiyo are dedicated to ending FGC in the Bohra community, and have already made great strides towards this goal through their work at the grassroots, raising awareness and holding “Thaal Per Charcha” (conversations over food) sessions, where people can talk openly about the practice in a safe environment.

The reach of the Faces for Change campaign will, Sahiyo hopes, extend beyond India. They are asking people to sign their petition calling for the UN to invest in research and support in Asia and acknowledge the global scope of FGC. The ‘UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme to Accelerate the Abandonment of FGM/C’ focuses primarily on sub-Saharan Africa with no focus on the Asian countries where FGC happens. As Insia states, the joint programme cannot look to end FGC by 2030, as is its mission, without ending it in Asia too.

At the Women Deliver Conference 2019 in Vancouver this June, Orchid Project and the Asian Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW) announced the launch of a new Asia network to support growing efforts to end female genital cutting across the continent. To get involved in shaping the network, please get in touch with ebony@orchidproject.org.